Over the last five decades, tens of thousands of children’s books have been published which paint pre-industrial civilization as, at worst, a prolonged and rustic camping trip, and at best a carefree and exciting, back to nature adventure – one devoid of the responsibilities and trials of modernity. All the while, modern children are being bombarded with every manner of negative cultural reinforcement about the sad, terrible and irreparably forgone state of present-day civilization. Children are having their worldview shaped from an astonishingly young age by both an unapologetically pessimistic media, and well-meaning but deeply misguided family, friends and the general public. The zeitgeist of our age is one of deep despair, “civilization has slipped from greatness and is getting steadily worse” it is as though we have collectively thrown in the towel on #HumanProgress in a resigned bid at least to go down laughing as civilization burns. This culture looks past civilization’s historical long run progress, seemingly wholly unaware just how far we have come as a species. This culture which is ignorant to, or discounts the progress of civilization has deeply impactful ramifications for developing minds. In rejecting rational optimism, progress and an entrepreneurial spirit to make the world a better place; and embracing a perpetually negative outlook of despair – we risk building an entrenched culture that embraces failure, entropy, stagnation and degradation as an acceptable natural outcome of human existence.

The state of civilization is, however, much better than it looks. Since the commencement of the Industrial Revolution, life expectancy, quality of life and overall living standards have improved dramatically the world over. From the United States to The United Kingdom and from Ethiopia and Bangladesh, people are living longer healthier, better fed and watered, more educated and more economically prosperous lives.

In the United States, life expectancy since 1800 has climbed from 39.4 years to 78.6 years, while GDP per-capita has grown from $1,980 to $56,700. Similarly, life expectancy in the United Kingdom improved from 39.6 years to 81.1 years and GDP per-capita from $3,280 to $40,040 over the same period.

While living standards in developing countries have improved at a slower rate than the most developed countries in the West, life is still improving across the board for developing and developed alike. Even from as late in the game as 1960, under-five child mortality has fallen dramatically across the world. Child mortality dropped from 25% in India and Bangladesh in 1960, to <4% by 2019 and from >24% in Ethiopia to <6% in 2019. It’s a largely similar story for nearly all of the developing world.

Since the dawn of industrialization, improving living standards have prevented hundreds of millions of families from losing one or more children in their family.

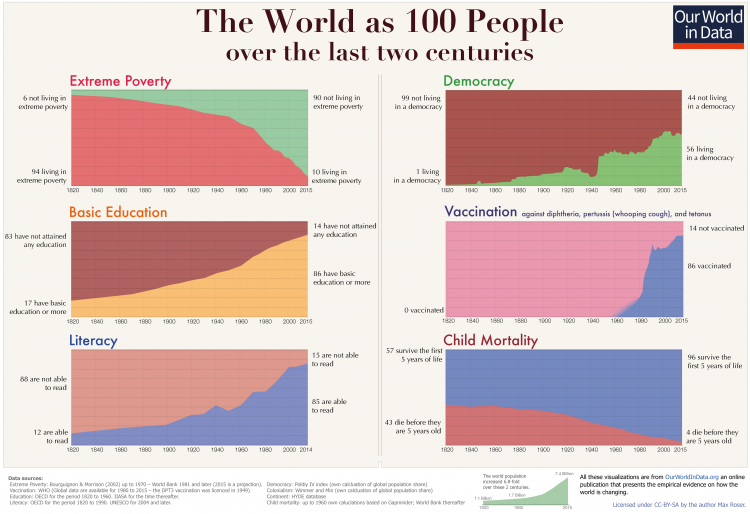

But it’s not just child mortality that has been dramatically reduced for the better – as a general trend, extreme poverty has been in a steady decline since the 18th century. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, 89% of the global population lived in extreme poverty; today it’s less than 9% and, on average, still improving. Literacy rates amongst the pre-industrial population were little better; at least 87% of men and women, and nearly all children were illiterate, that number has since fallen to 14%. As Max Roser from Our World In Data put’s it, “In 1820 only every 10th person older than 15 years was literate; in 1930 it was every third and now we are at 86% globally. Put differently, if you were alive in 1800 there was a chance of 9 in 10 that you weren’t able to read – today more than 8 out of 10 people are able to read.”

All told, global living standards have improve dramatically, and this fact is captured astonishingly well in books such as Progress, by Johan Norberg (2017), Factfulness by Hans Rosling (2018), The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves, by Matt Ridley (2010), Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, by Steven Pinker (2018) and At Home: A Short History of Private Life, by Bill Bryson (2010).

The story of human progress is also poetically and informatively told by Brad Harris in his excellent podcast series, How It Began: A History of the Modern World. And last but not least in the many excellent data sets from Our World In Data, and perhaps the most important graph in the history of civilization, provided by the team at Gapminder.

There has never been, however, a children’s book published on the history of human progress; one which shows in an appropriate manner, just how much better life is in the modern age. I stumbled upon this opportunity while reading my 6 year old daughter, and 3 year old son, editions of Look Inside, The Stone Age and Look Inside, Living Long Ago, from Usborne Books which my children loved and I do recommend. While I genuinely enjoyed the books, what stood out, besides how artificially joyous and lovely the pre-industrial world is portrayed – was how little was said on the forces which fostered and drove progress. In addition, each age is portrayed as essentially a different flavour of generally good, the Stone Age looked just as much fun to live in as the Bronze Age or Iron Age or the Industrial Age. What is lacking is for someone to write a children’s book showing the progress of civilization. To carefully thread the needle of storytelling the reality of life in the pr-industrial world without traumatizing or nauseating. How for example to do you convey conditions like the Indian famine of 1630 to 1631 as Steven Pinker quoted in Enlightenment Now. “Braudel recounts the testimony of a Dutch merchant who was in India during a famine “Men abandoned towns and villages and wandered helplessly. It was easy to recognize their condition: eyes sunk deep in the head, lips pale and covered with slime, the skin hard, with the bones showing through, the belly nothing but a pouch hanging down empty …. One would cry and howl for hunger, while another lay stretched on the ground dying in misery.” The familiar human dramas followed: wives and children abandoned, children sold by parents, who either abandoned them or sold themselves in order to survive, collective suicides …. Then came the stage when the starving split open the stomachs of the dead or dying and “drew at the entrails to fill their own bellies.” “Many hundred thousands of men died of hunger, so that the whole country was covered with corpses lying unburied, which caused such a stench that the whole air was filled and infected with it. In the Village of Susuntra …. human flesh was sold in the open market. Obviously there’s no version of the above which is suitable for a children’s book, however, we can undoubtedly do better at explaining the upward curve of food prosperity through the ages. I believe it is possible to tell the contrasting story of human progress for children in a manner which is engaging and honest, but not overwhelming.

It is at this stage in the article, where I must say I have undertaken this challenging, and hopefully rewarding project. Writing the first children’s book on human progress is an undertaking I’ve been working on for some time, however, many roadblocks still lay ahead.

We received a small grant from a benefactor of means who is passionate about human progress, however, finding a publisher to help bring the book into fruition remains, at least for the time being, elusive. Not to mention we still need to complete the planning, researching, writing and illustrating.

What can be said definitely is that there is a moral imperative to write such a book. The progress of civilization is not complete, there is still much work to be done in bringing improved prosperity to the world. Civilization needs engineers to bring abundant and inexpensive energy, chemists, genetic specialists and agriculturalists to bring secure, diverse and affordable food, industrialists to build factories and supply goods, laboratory technicians, welders, researchers, aircraft maintenance crew and a million other jobs that contribute to human progress. I hope at least in part, and to a very modest degree, that this book, should we find a publisher, encourages children to get out there and help improve the world; lifting living standards for the next generation. If you want to help to project, please consider sharing this article and following along on Twitter.

Author : Tony Morley is a writer, thinker, researcher, progress, growth and industrialisation exponent and an Energy Project Manager based in Sydney Australia.

9 comments